SANS TOIT NI LOI, OR HOW TO ACCOMMODATE A WHALE IN PAINTING

In a recent poem, Cynthia GirardRenard imagines a post-apocalyptic world where people ride unicorns on the streets of Montreal, beluga mothers sit in parliament in Quebec City, and all the houses across the province are covered in monarch butterflies. In this dream “there are no more planes, but blue whales and the great rorquals take us on journeys to the South Seas.”1 It’s not a question of escaping the harsh Quebec winter by lounging in the tropics. Instead the poem reinvents our modes of being and existing in the world through new alliances with other living creatures—whether real or imaginary, since, as Girard-Renard points out, “the end of the world came such a long time ago.”

How can we find our bearings and live together when the common reference points are being constantly disrupted? Philosopher Isabelle Stengers proposes that we “think from the starting point of devastation” by mobilizing both an activist engagement and a series of healing gestures informed by a culture of storytelling. She defines ecology as a “practice of observation, attention, and imagination”2 that transversely connects the environment to social life and subjectivities. This is precisely what Girard-Renard has been investigating for more than twenty years through painting and poetry: an energetic practice that invents colourful and unique spaces to revitalize—never moralize—our imaginaries; a joyfully anarchist work that describes the interactions, friendships, and desire possible between all kinds of humans and animals, but also between all kinds of pictorial styles, histories, and cultural practices, all done in the name of an eccentric and voluptuous hospitality. Observation, attention, imagination: the artist invites us to experience these very states as we enter her radical fairylands.

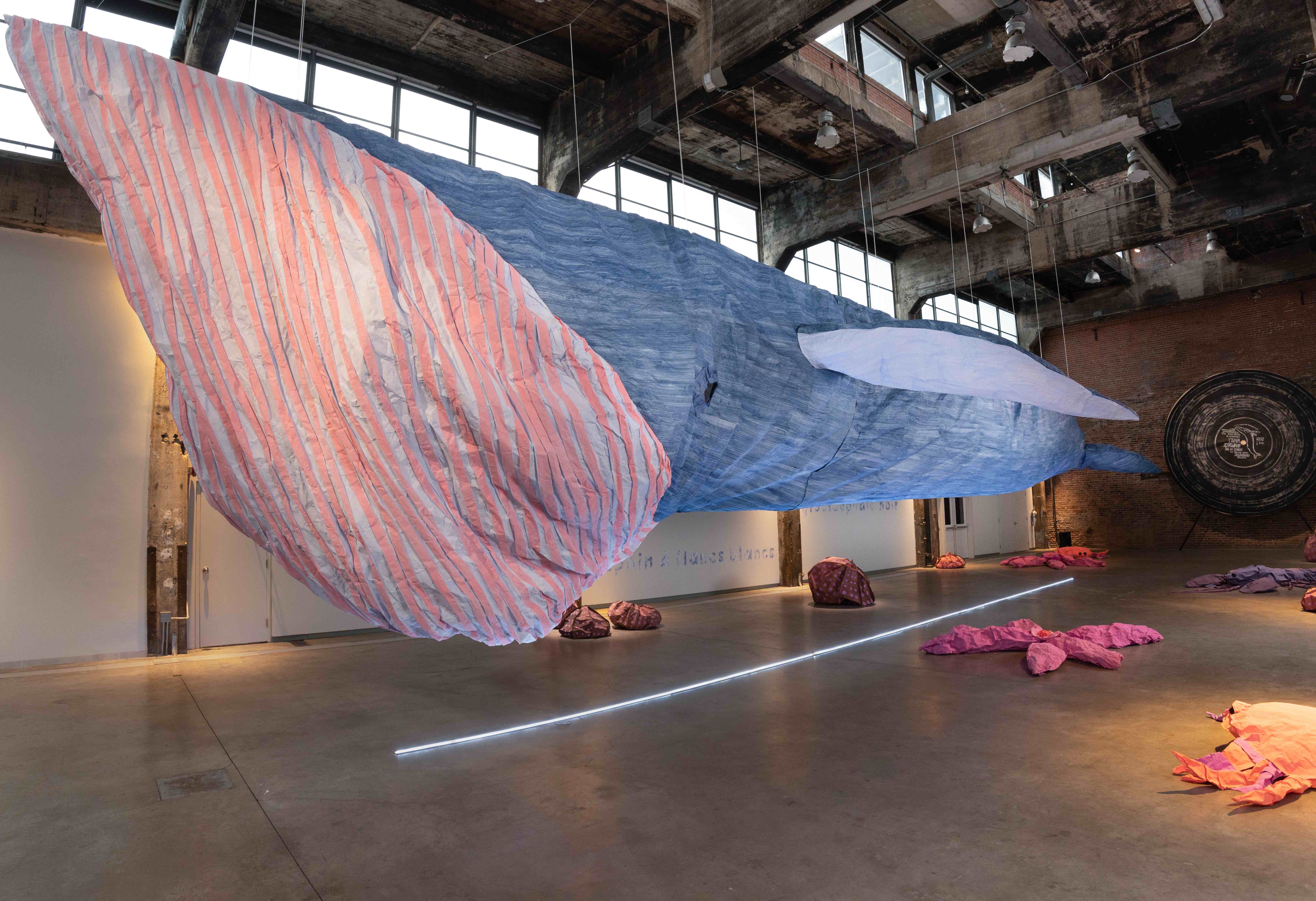

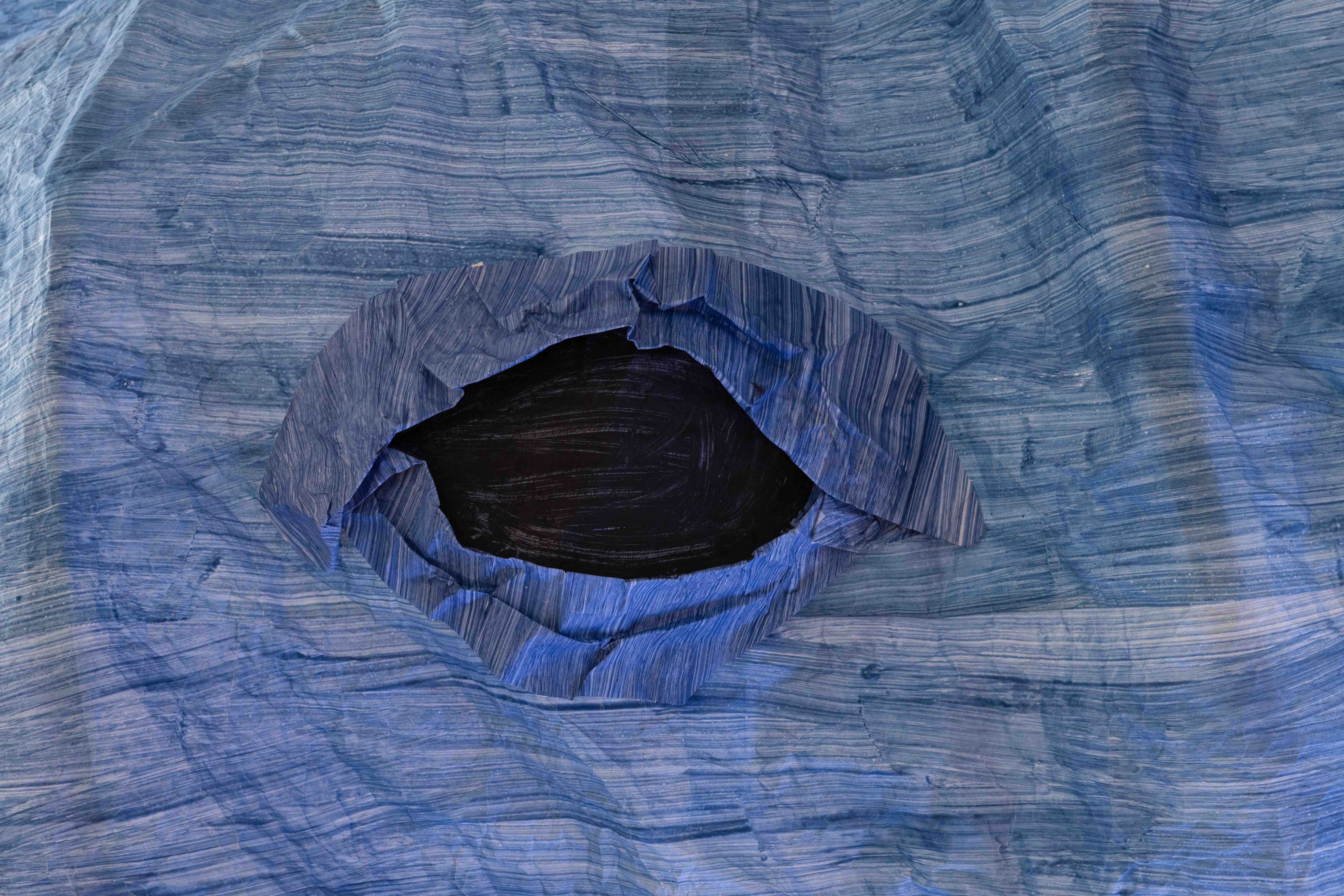

How does one go about accommodating a blue whale in the space of a painting? The answer is self-evident: one needs to take the painting outside of its frame. Particularly since we’re not talking about miniaturizing the largest living animal on our planet for the convenience of a stretcher on a human scale.3 In Fonderie Darling’s Main Hall, the artist has suspended a life-size mobile of a blue whale whose slender body—twentyone metres in length—becomes the imaginary standard of the industrial space. This monumental yet rigorously to scale sculpture produces a kind of spatial collage between two realms that would have never met if it wasn’t for the proximity of the Saint Lawrence River—a seasonal home of the solitary whale and a shipping route for human production and commerce. The sculpture isnonetheless a painting: 1 500 ft2 of monochromatic blue hand-painted on Kraft paper, then sewn and mounted on bamboo hoops. A painting reaching outside itself, throat hemmed with pink, in ecstasy.

However, rather than focusing on the technical feat, Girard-Renard is more interested in creating an environment conducive to an interspecies encounter. To achieve this, she has imagined an experimental theatre of colour, paper, and sound in the style of a temporary set for a travelling circus. Here, a variety of interfaces, combining fantasy and archive, activate our real and imaginary relationships with whales, manoeuvre our memories, and thwart our habitual ways of thinking, as though we needed to trigger the stereotypes of whales lying deep in our minds in order to come closer to the animal.

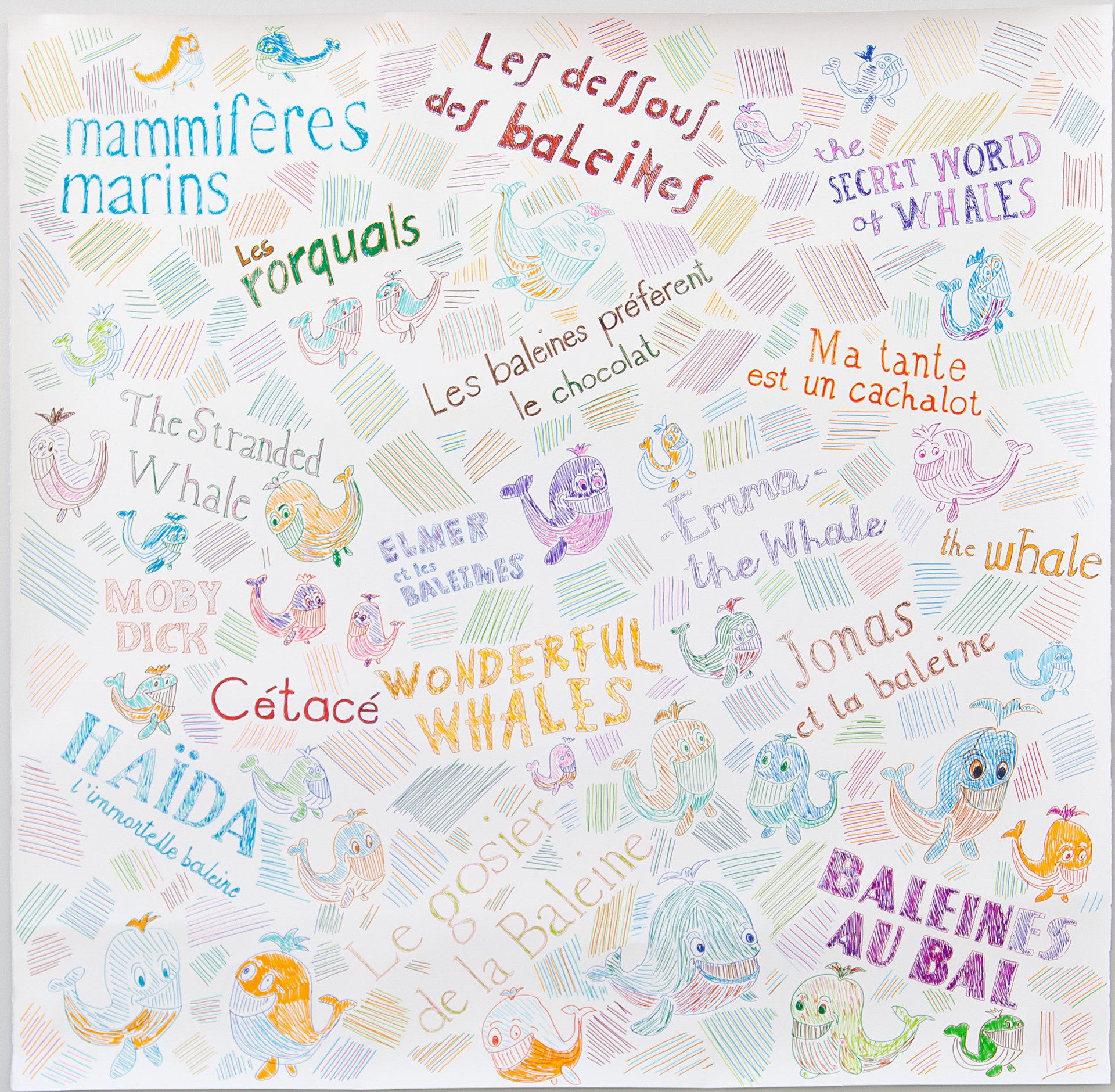

At the entrance of the Main Hall, a drawing is hung on the wall like a wild poster. In it dance, with a dizzying all-over style, a school of whales sketched on the fly, colourful crosshatching, and eye-catching titles— Wonderful Whales, Ma tante est un cachalot, The Secret World of Whales, and Les dessous des baleines. Yet we’d be hard-pressed to decide whether these half-emoji, half-graffiti whales are promoting illustrated children’s books, baring their baleen at us, or protesting for their rights, venting their blowholes and brandishing slogans— Les baleines préfèrent le chocolat [Whales Prefer Chocolate]!

The gallery floor is constellated with light paper sculptures: polka dot sea urchins, crumpled fuchsia starfish, a purple lobster, and coral-orange crabs. A variety of marine life that would enchant us if it wasn’t oversized and didn’t radiate toxically vibrant colours. To make sure that nothing stays too tidy, giant bottles of mineral water have spilled on this ocean floor. And some of the sea urchin shells intermittently hum noises of drills or rumbling engines. Is this the result of “the end of the world [coming] such a long time ago”?

We are walking on the ocean floor, experiencing a perspective that someone on a whale watching cruise could never know. In the end, while the whale may have come on human soil for a temporary visit under Fonderie Darling’s roof, the artist made sure not to turn it into a tourist attraction. There is no spray to watch out for. No acrobatic splash to expect. The paper whale is the one that hangs over our heads, not the reverse. We are walking on the ocean floor, head upturned, our eyes sometimes drawn to the nomenclature of marine mammals populating the Saint Lawrence, the letters of which sparkle on the walls like the reflections of light on water. And for a long, long time, we slide along the underbelly of this sovereign being, at once free and an outcast just like the female drifter haunting Agnès Varda’s 1985 film Sans toit ni loi.4

From the moment we entered, we began hearing the slow and powerful vocalizations that fill the whole space. They are the calls of humpback whales, raised to the top of the vinyl album charts in the 1970s, thanks to the worldwide distribution of an LP produced by the National Geographic. Songs of the Humpback Whales (1979) is closely reproduced, larger than life, in a sculpture installed against the brick wallat the back of the Main Hall: set vertically, the massive black disk spins with a continuous and hypnotic motion, as though amplifying the echo of the invisible travelling companions of the solitary whale, taking us beyond Fonderie Darling’s walls, projecting us into the vastness and making us, literally, lose our footing.

Beyond her own artistic universe, Girard-Renard is committed to creating dialogue between others’ explorations and her own research on the cetaceans of the Saint Lawrence, the first part of which makes up the current exhibition. In a gesture of hospitality and polyphonic assembly that is customary for her, she has invited artists from different disciplines to share their reflections and enrich our collective imaginary of marine mammals and ecosystems. Mary Anne Barkhouse, Geneviève Dupéré, Maryse Goudreau, Isabelle Hayeur, Ida Toninato, Susan Turcot and, thanks to a collaboration with Guillaume Lafleur and the Cinémathèque québécoise, other artists and filmmakers will make their voices heard for the duration of the exhibition, answering the whales’ call by prolonging the resonances and offering reference points that will hopefully contribute to strengthening our own practices of observation, attention, and imagination.

Ji-Yoon Han

Translated by Oana Avasilichioaei

*To access English subtitles, please click on the settings icon > Subtitles/CC > Select English (Canada)

[1] Cynthia Girard-Renard, “: loup / rat / gant :” in T’envoler, catalogue of solo exhibition of Myriam Jacob-Allard (Montreal: Dazibao, 2019), 15 (our translation).

[2] Isabelle Stengers, Résister au désastre. Dialogue avec Marin Schaffner (Marseille: Wildproject, 2019), 19–20 (our translation).

[3] Note the early appearance of a small beluga in 2003 in Girard-Renard’s La disparition: le béluga, la morue et les Expos [The Disappearance: The Beluga, the Cod and the Expos] (130 x 284 cm).

[4] While Varda’s film was released in English as Vagabond, the title (of her film and Girard-Renard’s show) literally translates as With No Roof or Law. (Trans.)

GRATITUDE

The artist would like to thank Xavier Bélanger-Dorval, Andréanne Hudon, Jackson Slattery, Catherine Boisvenue, Marley Johnson and the technical team at Fonderie Darling (Frédéric Chabot, Roberto Cuesta, Kara Skylling, Frédérique Thibault) for their essential assistance in the production of the works, as well as Jean-Philippe Thibault, Richard Noury, Frank Iervella and Gaétan Hamel. The exhibition is made possible thanks to the support of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC), Groupe de recherche et d’éducation sur les mammifères marins (GREMM), Prix Louis-Comtois awarded by the Ville de Montréal and a residency at Est-Nord-Est in Saint- Jean-Port-Joli.

Cynthia Girard-Renard

Cynthia Girard-Renard received her MFA from Goldsmiths College, London, UK (1998). Major solo exhibitions of her work have been organized at Musée d’art de Joliette (2017), the Uma Certa Falta de Coerencia, Porto, Portugal (2015), Esker Foundation, Calgary, Alberta (2014), and Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal (2005).

The artist has been the recipient of grants from the Canada Council for the Arts and the Conseil des arts et des lettres du Québec to partake in artist residencies in London, Paris, New York and Berlin. In 2018 she was the recipient of the Prix-Louis-Comtois for a mid-career artist, as well as the Takao Tanabe Painting Prize awarded by the National Gallery of Canada.

Girard-Renard’s work is found in numerous institutional collections, such as Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, the National Gallery of Canada, the Canadian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Carleton University Art Gallery, Galerie de l’UQÀM, Banque Nationale du Canada and Caisse de Dépôt et Placement du Québec. Cynthia Girard-Renard teaches at Concordia University, Montreal, where she lives and works.

Curator

Ji-Yoon Han