Montreal artist Barbara Steinman has been creating work for almost forty years in response to specific sociopolitical contexts and places, in art institutions, exterior spaces, and other more atypical ones such as an abandoned industrial building, a bank, and a chapel. While these interventions have often been called site-specific, the term “portable monuments,” [1] proposed by art critic Bruce W. Ferguson, describes them most accurately. Steinman is not so much interested in rooting her work in a specific place, but rather in altering the meaning of the work based on the site in which it is presented, making the lack of a fixed place—migration, wandering, exile, time shifts—the essential condition for creating work.

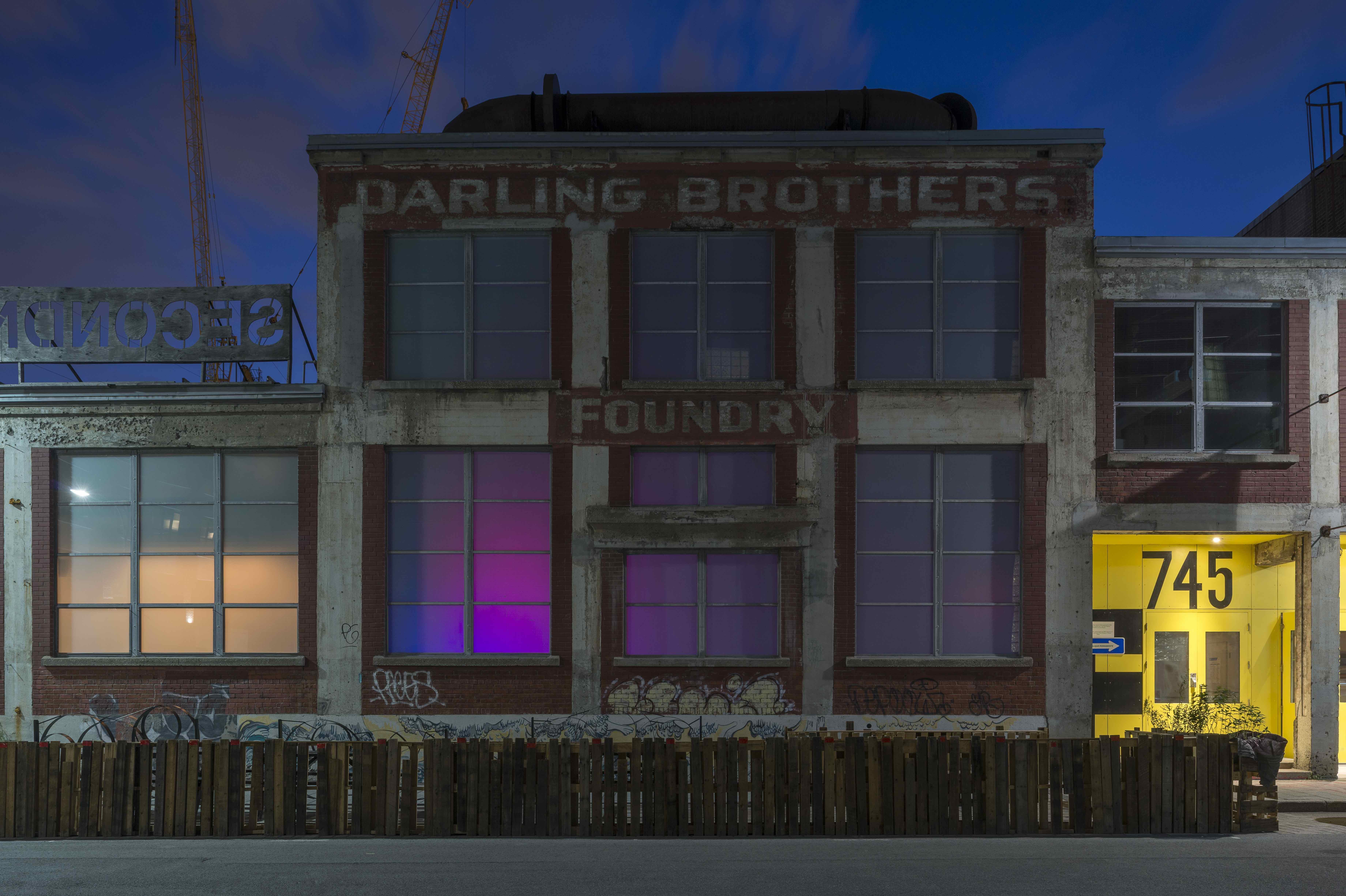

At the invitation of the Darling Foundry, Steinman offers a philosophical meditation on the monument-space of the Main Hall, whose volume embodies both the height of luxury and a kind of endangered species, in a neighbourhood that is being quickly and inevitably gentrified. In stark contrast to the fantasies of an “upscale” lifestyle promoted by new condo towers, but also to the expectations set up by the spectacular aspect of the exhibition space, the artist has created a series of “portable” interventions that examine the place and its inhabitability.

Careful not to take over the space and occupy its centre, Steinman uses her temporary stay in the Main Hall as an opportunity to draw a perimeter and demarcate a territory’s limits. With rigour, she has gone around the space, punctuating it with luminous traces. Yet defining this perimeter does not create an interior. Instead, it reveals thresholds and reference points. Visitors are not invited to circle the works, but rather to survey the emptiness, keep to the middle of the space, and in the words of e.e. cummings, “dive for dreams,”[2] for this is how we might take our place in the world and not be toppled by slogans and propaganda.

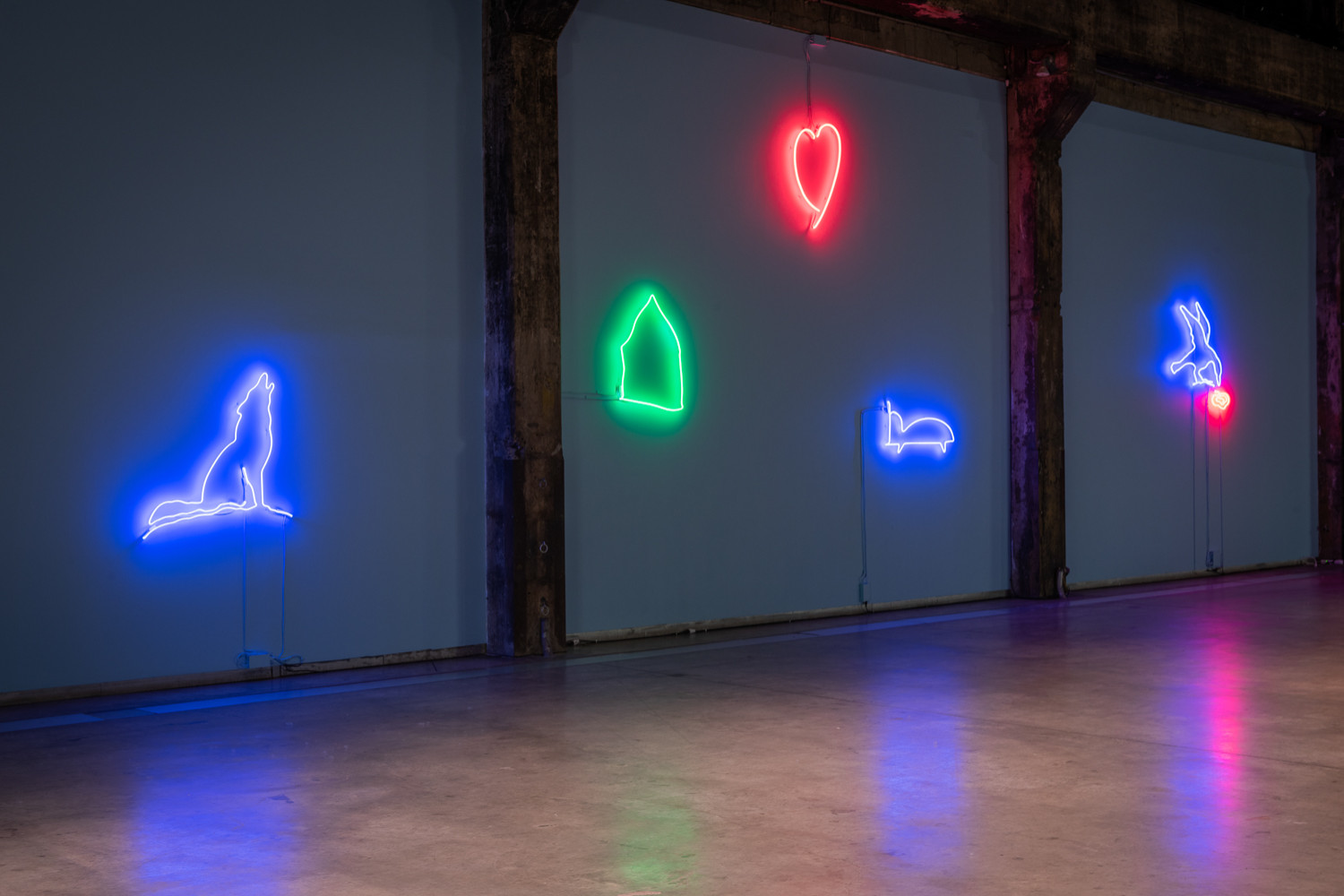

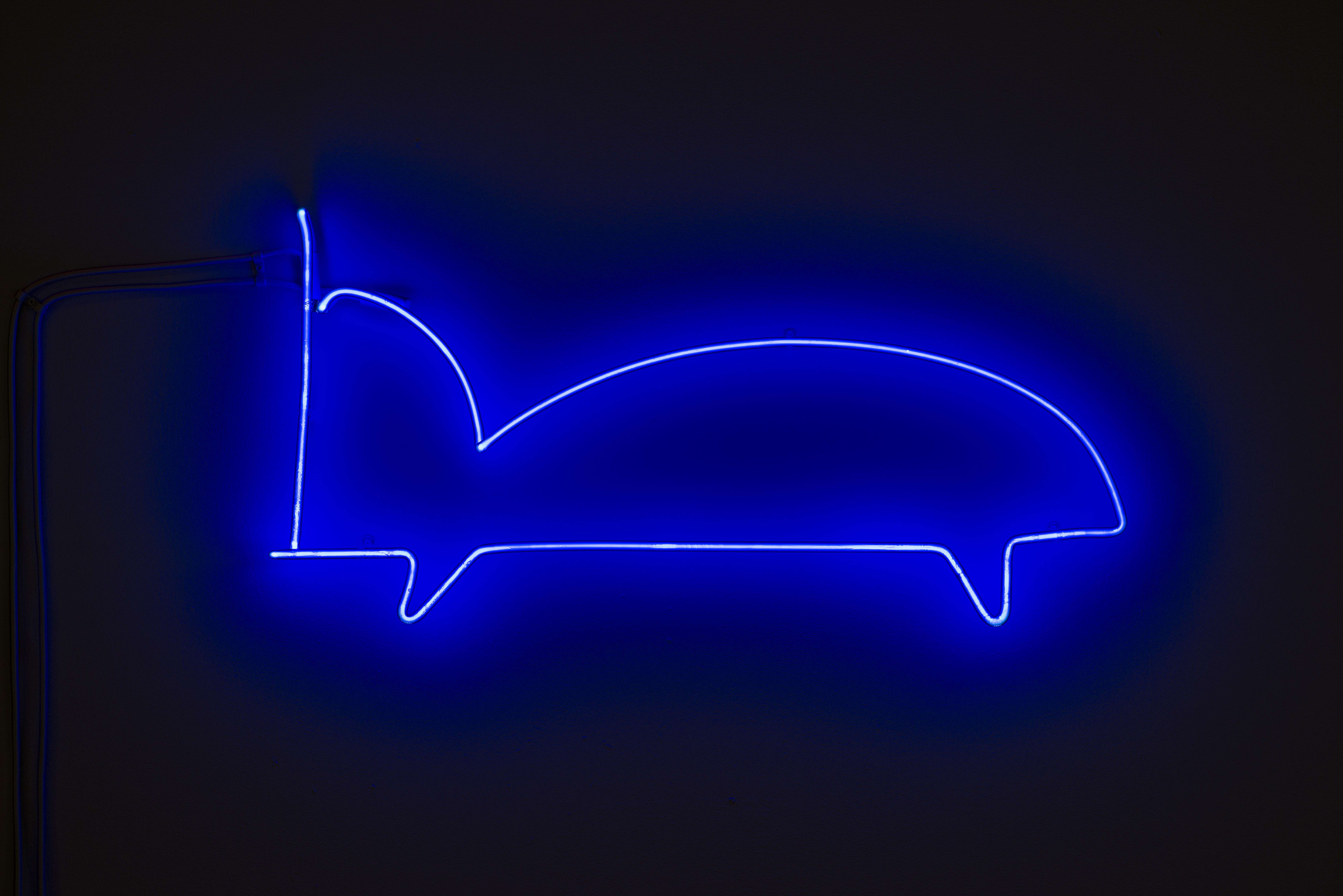

Diving for Dreams. Five neon drawings float on three sections of sky-blue walls—a gentle blue that at certain times of the day conjures the faded paint peeling off the Darling Foundry’s bricks and concrete columns and evokes its prior history. Functioning somewhere between a revival of the past and an imaginary projection, the work calls to mind a colourful rebus by associating quasi-childish drawings with figures of wild animals. Wolf. Home. Heart. Bed. Bird of prey. Some of the motifs are based on research, during which the artist asked people she met to make impromptu drawings in response to the word home. Using this open-ended collection of drawings, Steinman recomposed a series of neon graffiti that juxtapose the figurative with the schematic and symbolic, the animal with the human, the familiar with the untamed.

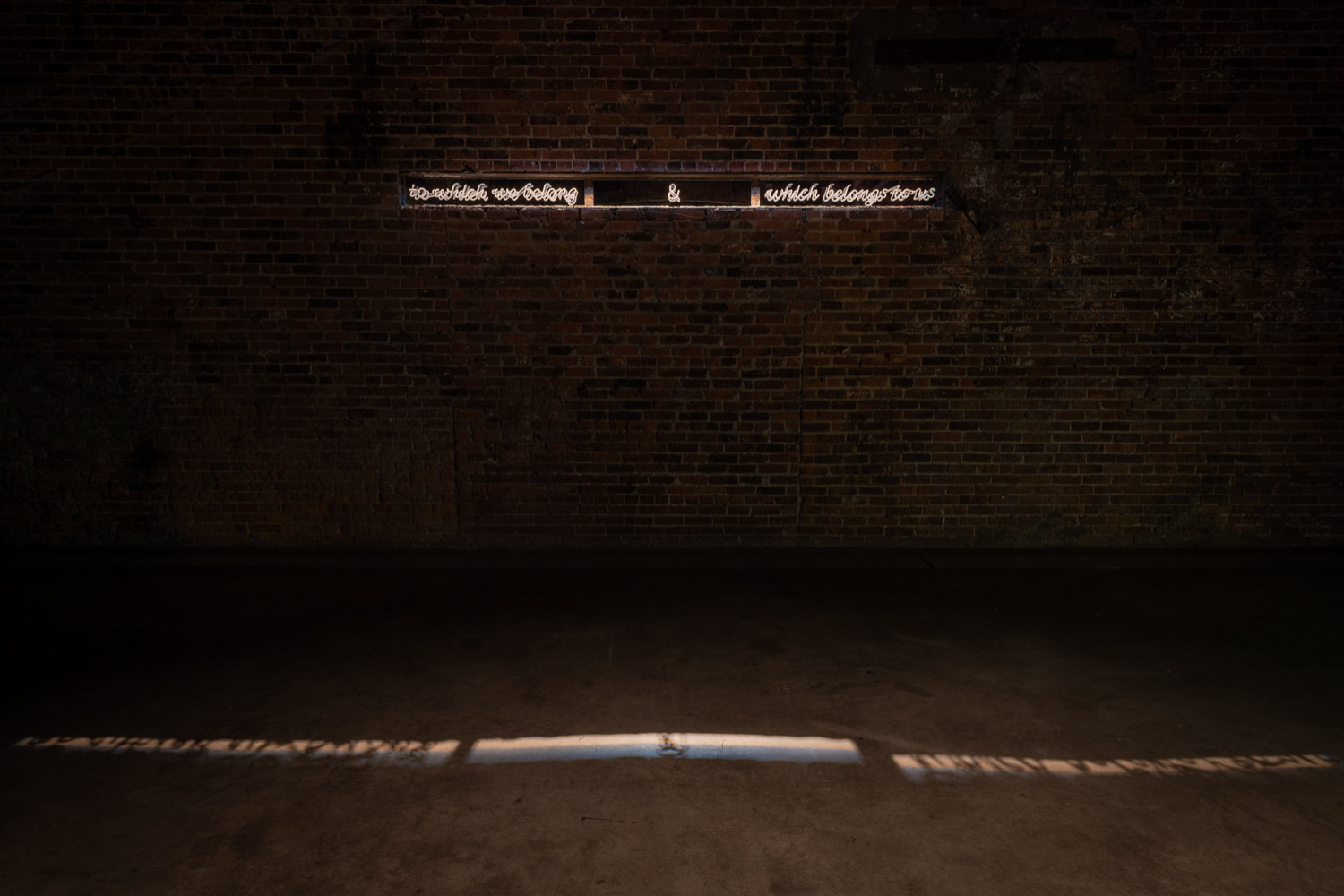

Niche. A work made of mirrors and glass is nestled in the crevice streaking the large brick wall at the back of the Hall, capturing light and animating the building’s entire palimpsestic envelope. Letters in white glass meander on the reflecting surface: “which belongs to us & to which we belong.” Charles Moore writes that the human need to “dwell” leads to the act “of connecting ourselves, however temporarily, with a place on the planet which belongs to us, and to which we belong.”[3] Being at home, therefore, is related less to having a fixed residence and more to relationships of reciprocity, interdependence, and intertwining. This is beautifully concretized here by the words in chiasmus and the twists of the letters, which from afar appear to be etched into the mirror and which seem to unravel as we get closer to the work. Yet who is this we asserting its belonging to the Darling Foundry’s walls? What community is being evoked here?

Day and Night (1989). A series of four staged photographs in light boxes depict an anonymous figure, face buried and resting, who seeks shelter in the exterior alcove of an industrial building dating from the same era as the Darling Foundry, and which was renovated as part of the development of the Quartier des spectacles. Initially created for the surrounding bays above the atrium of the contemporary galleries at the National Gallery of Canada, the work has been removed from its context and reconfigured on the floor, installed like a series of nightlights along the walls. By migrating her own works thirty years later, Steinman introduces into the dream space a counterpoint to the false candour of the neon drawings: images that are simultaneously historical and ageless, that seem not only to belong, but also to find a temporary resting place (along with the rest of the exhibition) in the space.

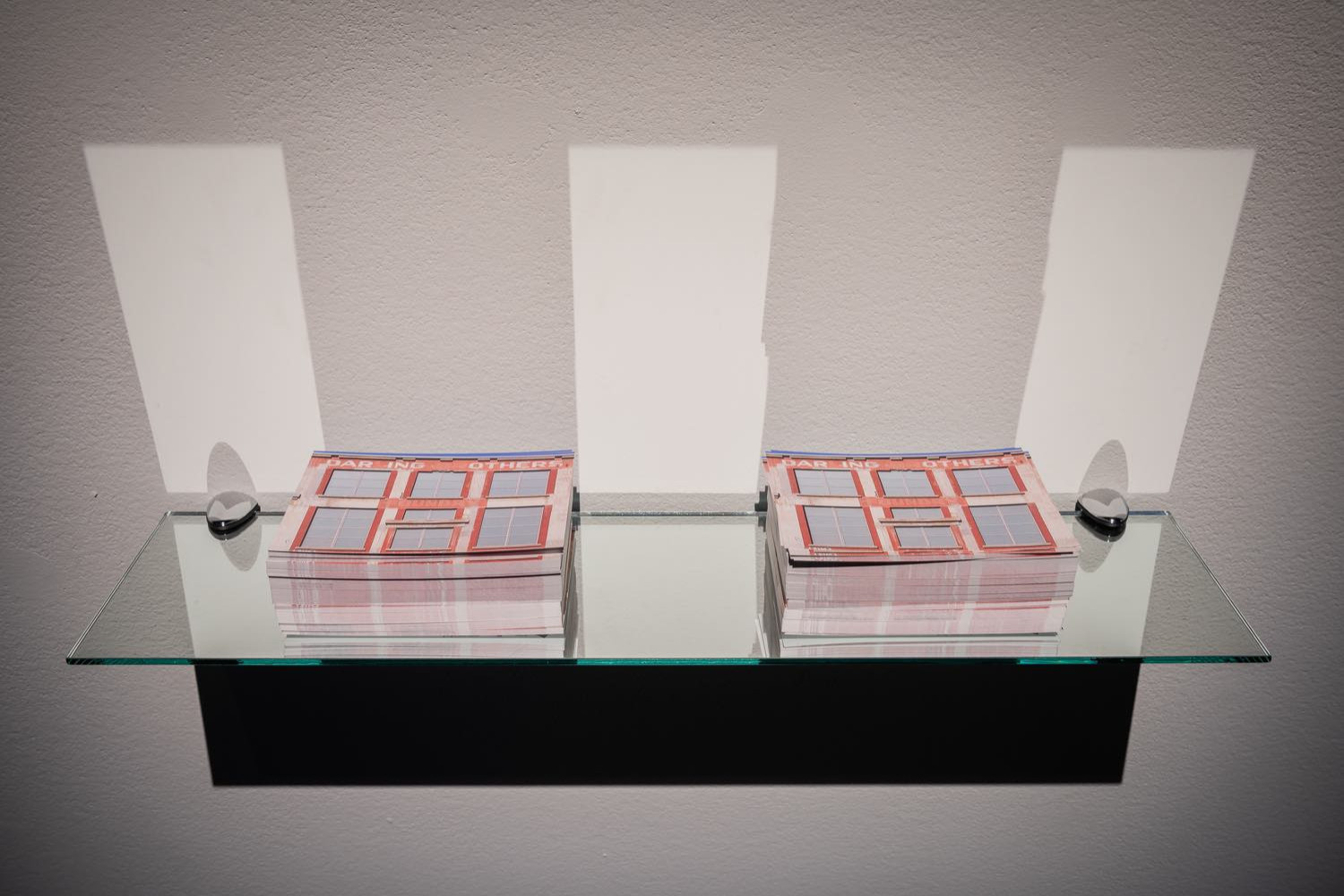

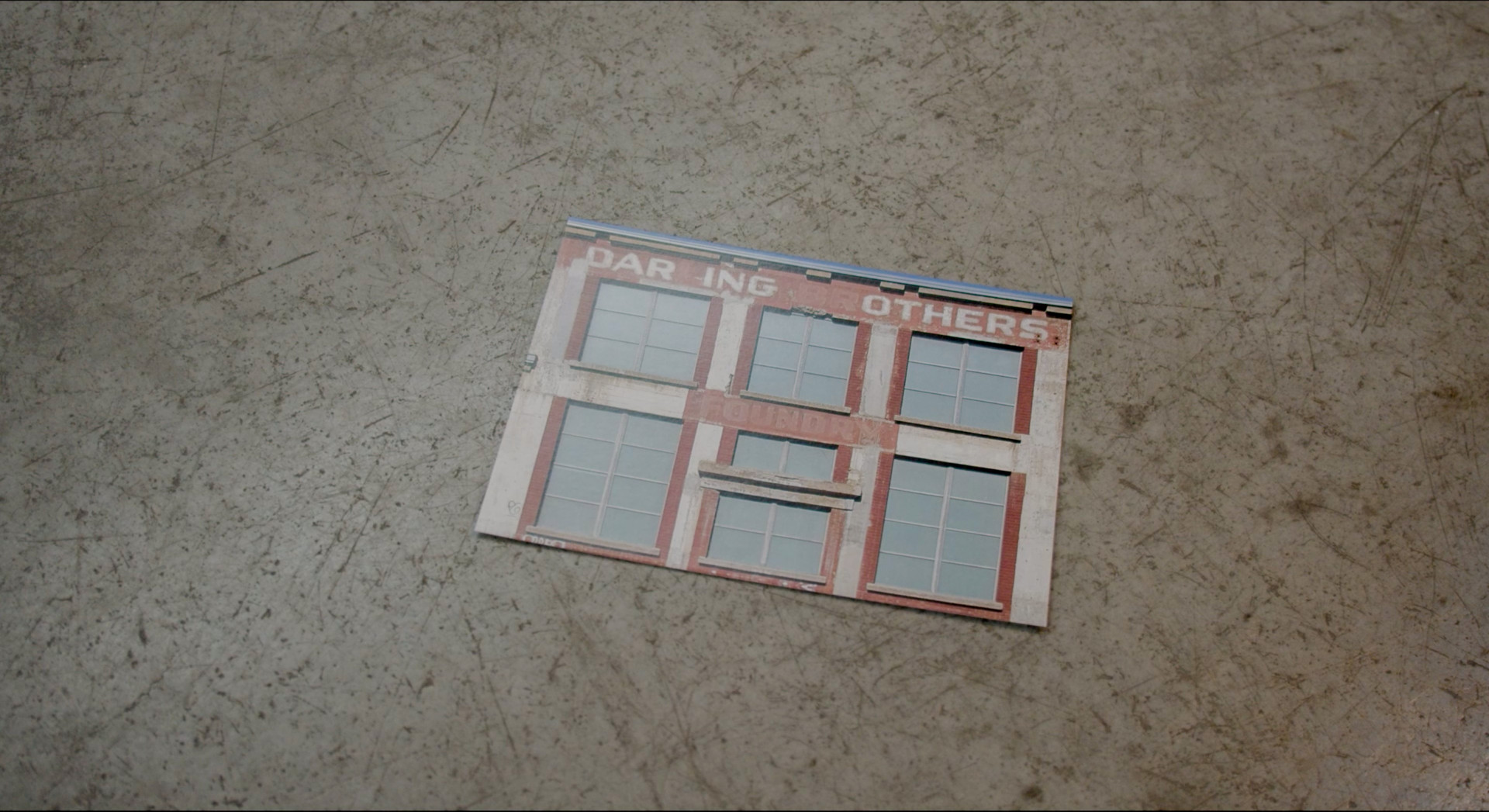

Daring Others (Photo Souvenir). Near the doorway, visitors can help themselves to a postcard illustrating a barely altered “souvenir” of the iconic facade of the Darling Brothers Foundry, reduced here to pocket-size format. Mirroring Niche, the photograph plays with the reversibility of the site’s surfaces by integrating the exterior into the exhibition space. Once again, it involves deciphering words: the reading is shaped as if by the wear and tear of time, as remnants of faded lettering linger on the adjacent building. In contrast to the sense of community and belonging invoked by Niche, the postcard ironically places some distance between the space and the mythical name that marks it: the Darling brothers are transformed into daring others, that is “bold or fearless beings”—although some might read “daring” as a verb, and the phrase as “challenging others.”

From one work to the next, we are continually brought back to the middle, to the interval of emptiness suffused with the constantly changing daylight or defined by the nighttime lighting, to the breath of this space fringed by light—neon, mirror, glass, light boxes. To dive for dreams has nothing to do with some phantasmagorical escape: such an act is more akin to the difficult labour of the pearl diver, a Shakespearean image taken up by philosopher Hannah Arendt to describe the work of collecting, citing, and salvaging the debris of the past undertaken by cultural critic Walter Benjamin.[4] Within the Darling Foundry, does Steinman not give rise precisely to such fragments scraped from the depths of time and history, from individual and collective memories?

Ji-Yoon Han

translated by Oana Avasilichioaei

[1] Bruce W. Ferguson. “The Art of Memory: Barbara Steinman,” Vanguard 18.3 (Summer/Spring 1989): 10–15.

[2] e.e. cummings. “dive for dreams,” Poetry 80.3 (June 1952): 125.

[3] Charles Moore. Foreword to Junichiro Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows (London: Leete’s Books Inc., 1977): 5.

[4] Hannah Arendt, Introduction to Walter Benjamin, Illuminations: Essays and Reflections (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1968), 7–58.

The creation of the works in the exhibition was made possible thanks to the financial support of the Conseil des Arts et des Lettresdu Québec. Day and Night (1989) is part of the permanent collection of the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa (purchased in 1990). The artist would like to thank David Merk, Alexandre Payer, Lorraine Simms, Angela Grauerholz, Gaétan Hamel and the technical team of the Darling Foundry for their assistance.

Barbara Steinman

Known for her multidisciplinary work, Montreal-based artist Barbara Steinman began her career in Vancouver as a video artist. At the beginning of the 1980s she was the co-director of artist-run centers Vidéo Véhicule and Powerhouse Gallery.

Steinman's works have been presented in numerous biennials and exhibitions in Canada, Europe, Japan and the US, among which the Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA), the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, the Art Institute of Chicaco, and the National Gallery of Canada. Steinman was the recipient of the Governor General's Award for her outstanding contribution to the fields of visual and media arts (2002). She received an honorary doctorate from the Fine Arts Faculty of Concordia University in Montreal (2015). Her work is represented by Galerie Françoise Paviot in Paris and Olga Korper Gallery in Toronto.

Curator

Ji-Yoon Han